Download

Acceptance speech

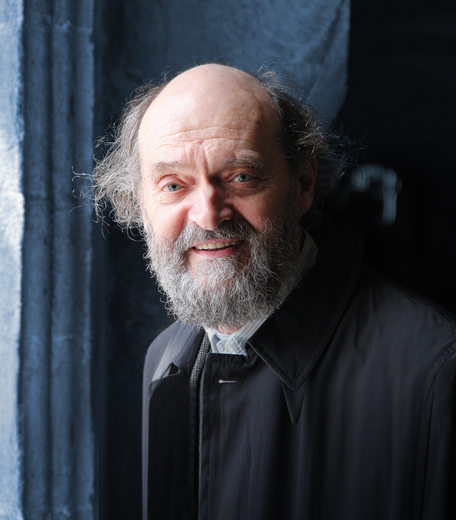

Arvo Pärt

Arvo Pärt was born in 1935 in Paide, Estonia, just four years before the country’s incorporation into the Soviet Union. He studied piano, flute, oboe and percussion before the age of twenty, when he made his first forays into composition.

In 1954 he began higher studies in composition at the Tallinn conservatoire, but had to break off his training for compulsory military service. By the time of his graduation year, he had attained a formal mastery evident in his Symphony No. 1 (1963), written while he was working as a sound engineer for a state radio station. Some of the output of his student years still forms part of his official catalog, including orchestral pieces like Nekrolog (1960) or Perpetuum mobile (1963): “A good number of extraordinary works,” that flow from “a profound exploration of the modernist vocabulary,” in the words of committee chairman Paul Hillier, Artistic Director of the Theatre of Voices (Denmark).

The music he went on to create in the late 1960s stands out for its distinctive use of the collage technique, darker and more dramatic, with a clear indebtedness to the Baroque tradition, in compositions that reflect an internal struggle between two competing worlds. This inner dialogue would find its fullest expression in Credo (1968), which marked a turning point in his life and work.

Credo’s premiere was an epic event for the public in attendance, who would not stop cheering until the piece was played again in its entirety. The Soviet regime saw a threat in both the work and its composer for their innovating spirit and ability to convey a spiritual truth that connected with listeners.

Pärt responded by embarking on a return to the origins, studying Christian vocal music, Gregorian chant, the Notre Dame School and Renaissance polyphony. This period coincided with two milestones in his personal life: marriage to Nora, his inseparable partner, and his official reception into the Orthodox Church.

His own path: ’tintinnabuli’

Pärt’s output in these years was thin, despite including some major works like his Symphony No. 3 (1971). Then in 1976, with the short piano piece Für Alina, he re-emerged with a radically distinctive voice.The two worlds that Pärt had been exploring found their perfect outlet in a new technique called tintinnabuli. Two musical lines stripped of all accessory elements. The Artistic Director of the Gran Teatro del Liceo in Barcelona and committee secretary Víctor García de Gomar defines it as “the invention of a musical grammar that is uniquely of itself, comprising repetitive sequences of a certain contained energy, chords that overlay one another so that each shift is almost a miracle. They are subtle, but change their color in such a way that the whole meaning of the structure changes with them.”

In the forty years since then, Pärt has continued to develop the technique which would underpin all his subsequent production. Indeed the birth of this new language ushered in an especially prolific year, 1977, when he wrote some of his most celebrated works: Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten, Fratres, Summa and Tabula Rasa. Committee member and conductor Pedro Halffter describes these works as imbued with a “personal, communicative language that has fascinated both the most demanding and the broadest publics. His music is admired, recognized and performed by the world’s leading musical and cultural institutions.”

The human voice as a perfect instrument

The premiere of Tabula Rasa was another event, this time in Tallinn, which extended his fame beyond national borders. His growing influence and popularity with audiences, his radically individual artistic voice and his religiosity were considered a threat by the Soviet regime, whose attempts at interference led Pärt to take a public stance. He was detained at Moscow airport, accused of dissidence, and the press began denouncing him as a “traitor to the Motherland.” Finally the Soviet authorities recommended that he leave Estonia.

He went into exile with his family in January 1980, living first in Vienna and then in Berlin, where he would remain for almost thirty years. In Estonia, meantime, performances of his works were banned.

For Pärt, the textual element is enormously important. This is evident even in his instrumental pieces, where the word features heavily, drawn almost always from liturgical texts or prayers. However, it is his vocal music that most powerfully reflects this predilection for the textual – he has repeatedly stated that the human voice is the most perfect instrument – and that has won him the acclaim he enjoys on the global stage. The chair of the committee, Paul HiIlier, rates him one of the most important contemporary composers of choral music. Pärt’s vocal output includes such major orchestral works as Passio (1982), Stabat Mater (1985), Te Deum (1985), Miserere (1989/1992), Como cierva sedienta (1998/2002) and In principio (2003).

Germany would prove a richly fertile period in Pärt’s output, thanks in no small measure to his professional relationship with Manfred Eicher, whom he met in 1984. The founder and producer of music label ECM Records chose Tabula Rasa to inaugurate a successful series of new recordings, which took Pärt’s music to audiences around the world. His works began appearing in the programs of top international festivals, orchestras and ensembles, and in radio and TV broadcasts.

Estonia was restored to independence in 1991, and Pärt renewed his relationship with his home country, both personally and artistically. His music was again regularly performed, and the places he had passed through in his youth began celebrating tributes to him on his birthday. In 2010, he made the decision to move back, and has lived there ever since. That same year, he and his wife Nora founded the Arvo Pärt Centre, to house and maintain the composer’s impressive personal archive, while serving as a meeting place for musicians, researchers and music lovers everywhere.

“Arvo Pärt, who creates music of great purity and spirituality, is an oasis in a world oversaturated with technology. His music is an invitation to transcend individuality,” says Víctor García de Gomar. “Reserved and generous by nature, he chooses to be close to people, his fellow humans, and does not hesitate to place his art at the service of great tragedies.” The committee secretary is referring here to Da pacem Domine (“Give peace, Lord”), written two days after the events of March 11, 2004 in Madrid, a six-minute choral prayer which the composer dedicated to the 192 people killed in the terrorist attack.

Pärt’s music has connected with all kinds of public. “Both believers and non-believers are affected by its profound depth and sensitivity,” explains Robert Sholl, Professor of Music at the University of West London (United Kingdom) and also a member of the award committee.

In the words of the citation, “it is no exaggeration to say that Pärt’s work is constantly being performed somewhere in the world.” His versatility and expressiveness have also found an outlet in film, and his music features in hundreds of titles by directors like Paolo Sorrentino, Víctor Erice and David Trueba. Two albums by the Estonian composer have been winners of a Grammy, and for the last eight years the largest database of live classical music performances, published by the magazine Bachtrack, has listed him as the world’s most widely performed living contemporary composer.