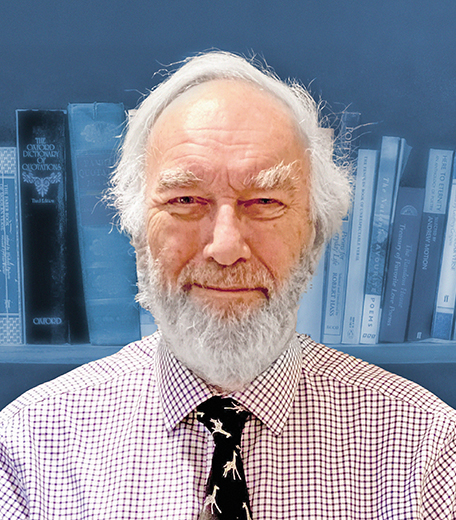

BIO

Ian Burton (Derby, United Kingdom, 1935) is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Toronto (Canada), where he has spent his academic career after earning a PhD in Geography (Resource Management and Natural Hazards) from the University of Chicago (United States). Author of ten books – outstandingly Environment as Hazard (1978), whose conclusions are every bit as relevant today – and more than 200 articles in scientific journals and reports, his research work has led him to participate in numerous national and international organizations.

In Canada, he has served as Director of the Impacts and Adaptation Research Group of Environment Canada, and Director of the University of Toronto’s Institute for Environmental Studies, among other appointments. Internationally, he has worked on three Assessment Reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, as well as on the IPCC’s Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters, and taken on consulting assignments for the World Bank, OECD, WHO and UNESCO. He currently serves on the Expert Advisory Committee of the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction’s Global Risk Assessment Framework.

CONTRIBUTION

While earlier editions of the Frontiers of Knowledge Awards have distinguished contributions to climate change science from the realms of modelling, physics or economics, this year’s prize recognizes the contribution of the social sciences. Specifically, the committee has selected three researchers who have pioneered the study of “how social conditions and culture shape our vulnerability to climate change and our ability to adapt,” in the words of the award citation.

In recent decades, scientific evidence has consistently shown that climate change is advancing at a faster-than-expected rate. This knowledge has also served to design future scenarios that help predict the effects of climate change in different regions of the planet, and how it might impact their populations.

Geographer Ian Burton (Derby, United Kingdom, 1935), Emeritus Professor at the University of Toronto, came to the issue of climate change through his research on natural disasters, and was the first to promote the “adaptation” concept to address climate change effects that, in the light of forecasts, are already unavoidable. From the first international climate meetings, he pushed this new area of research onto the agenda, seeking to define the best adaptation strategies in infrastructures, town planning, agriculture and architecture, among other domains; strategies, it was clear, that would run in parallel with mitigation efforts aimed at curbing greenhouse gas emissions.

By the mid-1990s, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) already numbered adaptation among the focus areas of one of its Working Groups, with Burton, alongside Adger and O’Brien, among its longstanding and most influential members. Subsequently, in 2013, the European Commission developed its own Climate Change Adaptation Strategy, which EU Member States, including Spain, have transposed at the national level.

Adger, Burton and O’Brien emphasize “the importance of interactions between environmental change and globalization,” and the need to “incorporate the cultural dimension” to the work of adaptation to climate change impacts that by now cannot be stopped. Research by the three laureates, who have collaborated on numerous occasions, has been instrumental in transferring knowledge to decision making, using analytical perspectives drawn from the social sciences.

For Miquel Canals, Director of the Department of Earth and Ocean Dynamics at the University of Barcelona (Spain) and a member of the committee “the awardees document the human dimension of climate change in all its magnitude, ranging across health, well-being, inequality, the vulnerability of whole nations, demographic changes, migrations… all major issues of our time whose connection to climate change we habitually ignore. Their contributions are also a window onto the future, one where the global effects of climate change will undoubtedly be worse. In other words, they put us, as a society and as individuals, in front of the mirror. Observing what that mirror reflects, and acting accordingly, is the responsibility of each and every one of us.”

Yet the concept of adaptation was not immediately or universally embraced. As Burton explained yesterday in a video conference after hearing of the award, those calling most urgently for mitigation measures – for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions – thought it counterproductive to talk of adaptation: “They argued that if you could mitigate there would be no need to adapt. But what I advocated, and was finding evidence for in my research, was that you need both adaptation and mitigation, because you wouldn’t be able to mitigate fast enough to avoid all need for adaptation.”

Burton alludes here to evidence in the latest IPCC reports to the effect that climate change is advancing at very different rates from those initially projected, “when climate scientists talked about a gradual process.”

Climate-induced migration

Neil Adger (Ballymena, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, 1964), who acknowledges Burton among his own inspirations, has centered his research on human migration, one of the key social effects of climate change. Much of the work of this Professor of Human Geography at the University of Exeter (United Kingdom) has involved data gathering on the ground, with surveys of local communities in countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh. His conclusions state that a population’s vulnerability to climate change depends not only on climate as such, but also, very directly, on social and political measures.

Speaking after the award decision, he stressed that although migrants rarely point explicitly to climate change as among the reasons for their move, they do cite the deterioration of traditional livelihoods like agriculture, often with a strong climate link.

Adger believes that a well as acting on natural spaces, adaptation strategies should focus on cities: “The most dominant flow of migrants is from rural areas to cities. And it is these flows that are being amplified by climate change, because it’s making rural areas less attractive. Cities are the crucibles for climate change adaptation; we need to make cities plan and prepare for climate change, so they become more resilient.”

Karen O’Brien (Aachen, Germany, 1963), Professor of Human Geography at the University of Oslo, is likewise concerned about impacts on vulnerable populations which, her research finds, suffer a double exposure to climate change and globalization. As she explains, “in the same way that double exposure in photography refers to two images that are overlain and create a blurry image, with this concept we express how the processes of globalization and climate change create uneven outcomes, in other words winners and losers. The two processes not only overlap but also create feedback that can accelerate or diminish them.”

Carlos Duarte, holder of the Tarek Ahmed Juffali Research Chair in Red Sea Ecology at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (Thuwal, Saudi Arabia) and committee secretary, considers the contributions of the three laureates to be “fundamental at a time when the green stimulus to reactivate the economy post-Brexit promises a rapid energy transition. It is vital that this transformation is accomplished without harming the vulnerable, not only in the world’s most disadvantaged regions but also in the developed countries, where the term energy poverty has become common currency now many governments have embedded the costs of transition to renewables as a fixed charge in electricity bills, affecting mainly households with unemployed parents, single-parent households and households of people with disabilities. Social justice must be a touchstone in climate change solutions, whether of adaptation or mitigation.”

O’Brien’s research also addresses the adaptation concept coined by Burton from a psychosocial and cultural standpoint. She talks of three spheres of adaptation to complete the transformation that climate change demands: “Climate change is an issue that goes beyond the environment; it is also a social and cultural challenge. Adaptation to the effects of climate change requires a profound transformation in three spheres – practical, political and personal – that also act upon each other. With the practical sphere referring to the technical and behavioral changes, the political sphere to the systems and the structures that shape our capacity to respond, and the personal sphere to our values and worldviews, both individually and collectively.”

For O’Brien, some of the most powerful levers for this transformation come from education, and from the media acting as disseminators of evidence-based knowledge on climate change.

A matter of “urgency”

The three laureates agree on the urgency of actions aimed at both adaptation and mitigation. As Burton remarks, “we should never underestimate the importance and the urgency of climate change.” In his view, “we are not doing enough in either mitigation or sustainable adaptation of a kind that doesn’t cause an even graver impact.”

Even so, he declares himself “cautiously” hopeful: “The youth movement is strong and there is a growing population awareness as people suffer or hear about others suffering wildfires, extreme storms and droughts in other parts of the world. But I also think that the private sector, which has long avoided expressing concern about climate change, is coming round to the idea, and I speak particularly of the large investors who are beginning to see that they have to start investing more in renewable energy.”