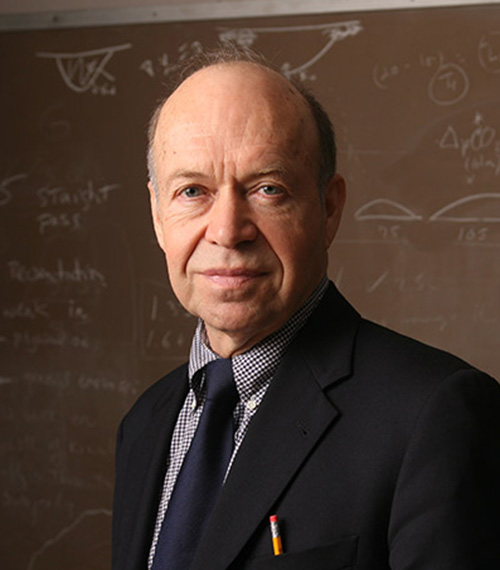

James E. Hansen (Denise, Iowa, United States; 1941) is an Adjunct Professor at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, where he has led the Climate Science, Awareness and Solutions program since the year 2013. From 1981 to 2013 he was Director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), where he spent his postdoctoral career after earning a PhD in Physics at the University of Iowa (1967). He also completed a brief research stay at Leiden Observatory.

He was part of the team responsible for the GISS terrestrial atmosphere model, a weather prediction tool that Hansen and his colleagues redesigned to provide long-term climate simulations. This model is being constantly upgraded in line with new findings and technological advances. In 1987, he and Sergej Lebedeff published GISS’ first global temperature analysis, which detected an increase in Earth temperatures between 1880 and 1985. In a 1988 paper, Hansen and his co-authors correctly predicted an acceleration in global warming with respect to the 1950s, foreseeing that its effects would be felt in the 1990s.

That same year, his testimony to the United States Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, based on his scientific findings, helped raise broader political and social awareness of the global warming issue, its human origins and the need to act now to mitigate its impact.

A member of the National Academy of Sciences since 1995, his multiple honors include the John Heinz Environment Award, the Roger Revelle Research Medal of the American Geophysical Union and the Leo Szilard Award of the American Physical Society, for Outstanding Promotion and Use of Physics for the Benefit of Society.

Speech

Climate Change 9th edition

The first ever global climate circulation model was programmed on a computer occupying a whole room and with only half a megabyte of memory. The year was 1969. The program was run for fifty days in the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory at NOAA (America’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) before finally delivering its results into the hands of researcher Syukuro Manabe. This is viewed as a milestone moment: the first mathematical simulation accurately recreating the global physical and chemical processes giving rise to climate. Manabe is now co-winner, along with fellow climatologist James E. Hansen, of the BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Climate Change.

The two scientists arrived independently at the first computer models integrating all major climate factors, and were able to predict how much Earth’s temperature would rise in line with increasing atmospheric CO2.

Syukuro Manabe (Ehime Prefecture, Japan, 1931) was a pioneer in applying the calculating power of computers to the climate domain. His initial goal was simply to improve meteorological forecasting, for at that time the climate change issue was not on the radar of science. The Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius had warned in the late 19th century that fossil fuel combustion would lead to planetary warming, but no one had yet heeded the call.

Manabe earned a PhD in Meteorology from the University of Tokyo in 1958. Not long after, urged on by the lack of opportunities in post-war Japan, he moved to the United States to work with a researcher at the U.S. Weather Bureau who, like him, was specialized in rainfall prediction. In 1963, he joined the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory at NOAA. The availability of computers meant Manabe could factor key climate elements into his models, among them water vapor, winds and atmospheric heat transport. To simulate the latter, however, he also had to input greenhouse gas effects, which drew his focus to CO2. By the end of the 1960s, Manabe’s model was predicting that if CO2 concentrations doubled, average world temperatures would rise by 2°C.

James E. Hansen had at the time just completed a PhD in Physics. His training had included a scholarship at NASA and stints as a visiting student in the Astronomy Department at the University of Tokyo, where he became acquainted with Syukuro Manabe’s work. In 1967 he joined the staff at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, researching on the atmosphere of Venus. Venus is not the closest planet to the Sun but it is certainly the hottest – up to 500°C – and his work there helped establish that these extremely hot temperatures are due to an exacerbated greenhouse effect.

This finding was to mark a turning point in Hansen’s scientific career. It was by then becoming increasingly clear that atmospheric CO2 concentrations were on the rise, and scientists were wondering what the effect might be. For Hansen, this signaled the moment to switch to the study of our own planet, given what he describes as “the unfathomable consequences for countless people of any variation in the climate.” His model indicated that world temperatures would rise by up to 4.5°C in the course of the 21st century.

His model indicated that world temperatures would rise by up to 4.5°C in the course of the 21st century.

TUITEAR

The paper he published in 1981 featured two innovations: it was the first to incorporate global temperature figures – thanks to a method of his invention for gathering data from available meteorological stations; and it also anticipated how warming would affect other processes, like oceanic circulation, the loss of Arctic ice cover or cycles of droughts and flooding.

Manabe and Hansen’s models are the forerunners of the dozens of climate models now in use, whose reliability scientists know they can trust. “Looking back on how the climate has changed in the last few decades, and how models have captured these changes, we can be pretty sure about their forward projections,” remarks Manabe, since 2005 Senior Meteorologist on the Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at Princeton University (United States). He warns: “It is very hard to say as of what temperature the change becomes dangerous. What we do know is that warming will be more dangerous if it exceeds 2°C, and the less the climate changes, the better for us all.“It is very hard to say as of what temperature the change becomes dangerous. What we do know is that warming will be more dangerous if it exceeds 2°C, and the less the climate changes, the better for us all. So we must do everything we can to minimize climate change.”

Hansen, Director of the Goddard Institute for Space Studies from 1981 to 2013, and currently a professor at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, points up the “first big conclusion” of his work: that climate is acutely sensitive to human action. The large variations in the size of the polar ice caps between glacial periods are due to small changes in the Earth’s orbit, and the climatic perturbation caused by the burning of fossil fuels is, he affirms, more powerful still. “The changes have started and there are more to come,” he cautions. “The last time the planet was one degree hotter was during the interglacial period, some 120,000 years ago, and sea level was between 6 and 9 meters higher than it is today. If we allow that to happen again, we will lose all our coastal cities.”