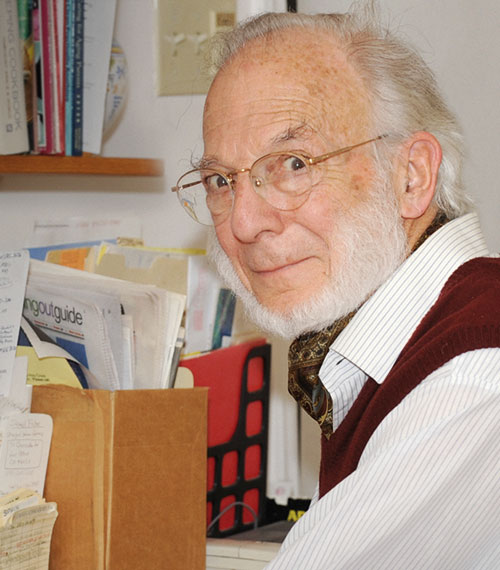

Michael E. Fisher (Trinidad and Tobago, 1931, of British nationality-2021) earned his PhD in Physics in 1957 from King’s College London, where he was appointed lecturer in 1965. The following year, he moved to Cornell University (United States) where he was successively Professor of Chemistry and Mathematics (1966-1973) and Horace White Professor of Chemistry, Physics and Mathematics (1973-1989), as well as chairing the Department of Chemistry from 1975 to 1978. In 1971, he was elected a member of the Royal Society and in 1983, of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. He joined the Institute for Physical Science and Technology at the University of Maryland in 1987.

Fisher’s many distinctions include the Wolf Prize (in 1980, jointly with Kenneth G. Wilson and Leo Kadanoff), the Irving Langmuir Prize in Chemical Physics (1971), the Boltzmann Medal of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (1983), the Lars Onsager Prize of the American Physical Society (1995) and the Royal Medal in Physics of the UK’s Royal Society (2005).

He passed away on November 26, 2021, at the age of 90.

The early scientific careers of Richard Zare (Cleveland, Ohio, United States; 1939) and Michael E. Fisher were illuminated by two of the last century’s great discoveries: the laser beam and the structure of the DNA molecule. Fisher was there on the ground when the breakthroughs came; in King’s College London, whose physics department was then a hotbed of cutting-edge research. The laser and DNA. Two discoveries that would influence the life courses of the Frontiers of Knowledge co-laureates in the Basic Sciences category.

Fisher was a passionate explorer of the workings of certain biological molecules, and the cell as an entity. Meanwhile, Zare developed laser-based techniques that allow researchers to view individual molecules for the first time. An advance whose revolutionary applications range from tracking the exact progress of chemical reactions – rather like watching a film still by still – to sequencing DNA itself.

Enthusiasm; the desire to share “the thrill of discovery,” as Zare puts it; and a seemingly endless appetite for intellectual adventure are remarks that come up frequently in descriptions of Richard N. Zare, who is also a dedicated teacher. “Build splendid sandcastles, the foundations will follow; without a dream, little can be accomplished,” he exhorts his students. “Teaching makes you question what you think you know, and that is what a researcher must do. Teaching is my secret weapon.” Certainly the formula has worked for him. Zare, Marguerite Blake Wilbur Professor in Natural Sciences at Stanford University, is the author of over 800 scientific papers and four books. He holds around fifty patents and served on the National Science Board, the policy-making body of the U.S. National Science Foundation, from 1992 to 1998, as an ordinary member and latterly as chairman.

The technique of laser-induced fluorescence, vital for the study of molecules and their interactions, is what has won Zare’s work its international reputation. The method involves exciting molecules by means of a laser beam then measuring the radiation they emit on returning to a pre-excited state. Thanks to this technique “now we can observe molecules one by one and track what they do in space and time.”

“Thanks to this technique “now we can observe molecules one by one and track what they do in space and time.”

TUITEAR

Laser-induced fluorescence has found applications in diverse fields, mirroring Zare’s own wide-ranging interests. “In my mind there is only one science. I let myself be led by what excites me, and I am a complete opportunist. I am willing to try any experiment provided I have the means of doing it and I think that its outcome could make a difference in how we understand the crazy world around us.” Zare’s professional history offers the best possible example of interdisciplinary endeavor.

After completing a double degree in chemistry and physics at Harvard in 1961, he obtained his PhD in chemical physics from the same university in 1964, still aged under 25, then after a short spell at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) joined the University of Colorado, where he worked in three separate departments – Chemistry, Physics and Astrophysics. In his next postings, at Columbia and Stanford, he was based in the Chemistry Department, although by then his research was taking him increasingly into biology. Since 2006, he has held the sought-after position of Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Professor.

One of the most newsworthy chapters in his biography concerned the Martian meteorite ALH84001, the subject of a 1996 claim by NASA that it contained evidence of extraterrestrial life. Zare’s group had found that samples of the meteorite contained a kind of organic molecule that forms in biological processes but also, for instance, in the burning of fossil fuels. This and other evidence was referred to in the NASA announcement. “I remain deeply interested in the topic,” says Zare, “and I want to keep an open mind about possible primitive life on early Mars until we go to Mars and find out.”

Zare’s current scientific agenda is full of imaginative challenges, ranging from counting the exact number of proteins in individual cells to the development of nanoparticles for drug delivery inside the body. “My list of pending problems is too long to relate here.”

Michael E. Fisher, Distinguished University Professor and Regents Professor at the University of Maryland (United States), shared Zare’s vision of science as having no fixed dividing lines as well as his unplanned career course. “You never know if what you are investigating will turn out to be a small island or a great continent. If, like me, you enjoy traveling and exploring, it is always a pleasant surprise to find another country beyond the one you know. Personally, I have always wanted to explore everything, but life is too short.”

Fisher figured for decades among the world’s most cited physicists, with one book and over 380 scientific papers to his name. But his colleagues prefer to emphasize other qualities in the new Frontiers of Knowledge laureate: a well-developed critical faculty and insistence on rigor that have made him guide and master to some of the leading scientists in his field. Although he spent the first years of his career at King’s College London, Fisher’s most significant contributions date from his time at Cornell University in New York.

While Zare’s work has allowed us to view molecules in isolation, Fisher’s field of study, statistical mechanics, deals with their behavior “en masse”. His contributions are essential to our understanding of the so-called phase transitions – such as water changing state or the magnetization of a metal. Fisher not only corrected the theory used for over a century to explain these processes, but also realized that his model could serve for many different systems. “Where one state of matter changes into another there is a very special point that has fascinated me for years.”

Fisher also became engrossed in problems of biology; in his case, the study of proteins that operate as molecular motors. “Each cell is like a little city, with this molecule that carries things around. In biology, you can conduct all kinds of incredible experiments, like hook a tag onto that molecule and see how it moves about within the cell. But how does it move? What is that molecule actually doing? The theory you need to answer these questions is also statistical mechanics.”