The Frontiers of Knowledge Award goes to Ajzen, Albarracín, Banaji, Greenwald and Petty for contributions that have revolutionized attitude theory and its practical applications

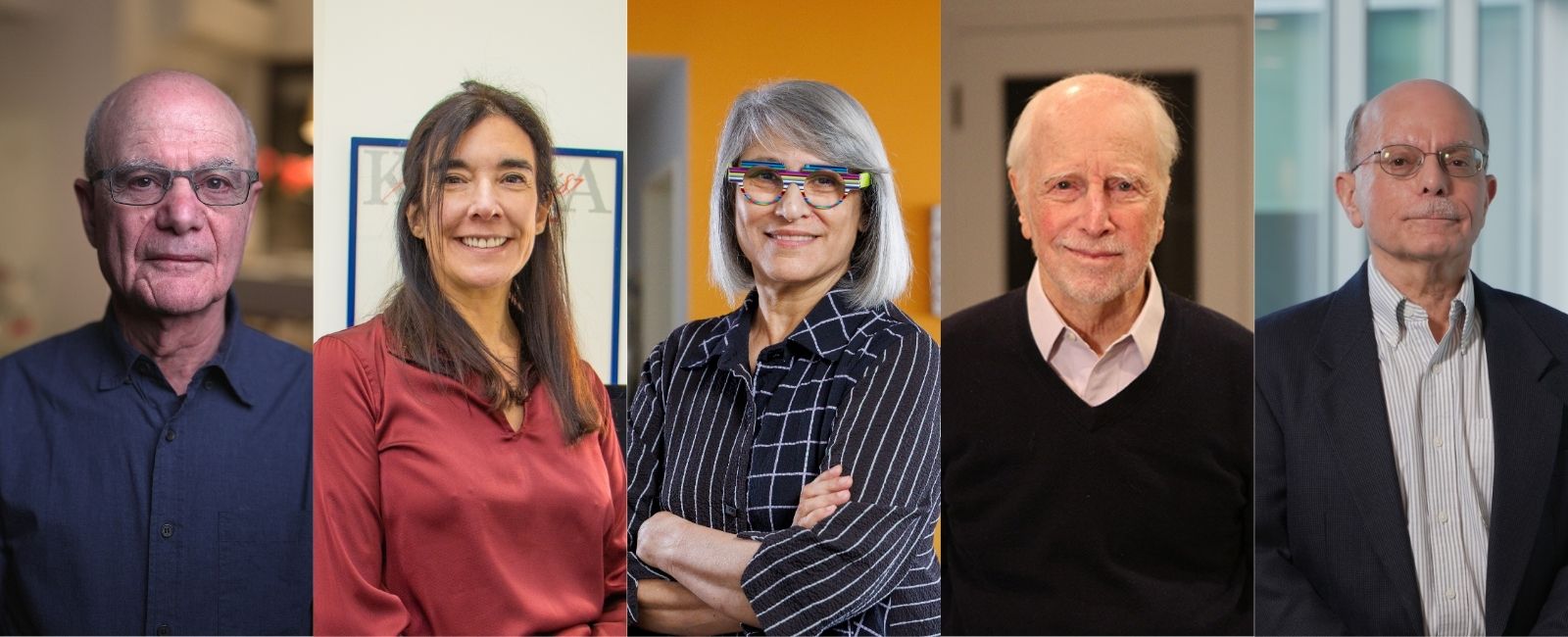

The BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Social Sciences has gone in this seventeenth edition to social psychologists Icek Ajzen (University of Massachusetts Amherst), Dolores Albarracín (University of Pennsylvania), Mahzarin Banaji (Harvard University), Anthony Greenwald (University of Washington), and Richard Petty (Ohio State University) for “revolutionizing the way we understand and measure attitudes” with an influence that extends to “psychology, sociology, political science, education, health, economics and other areas.”

11 March, 2025

The committee has distinguished them for their signal contribution to predicting and understanding human behavior through the lens of attitudes, elucidating how people are persuaded, and offering empirically corroborated explanations of how attitudes can be changed, in a combined body of work “spanning over five decades” that continues to resonate in today’s research landscape.

The award citation singles out the five scientists’ undisputed leadership in what is a cornerstone of social psychology: attitude theory and applications. The results of their research can help policy makers and other social agents “prevent negative societal consequences such as polarization, ethnic prejudices and unfounded stereotypes.”

Evaluations of people, ideas or things

Attitude study emerged as a strand within social psychology at the beginning of the 20th century, and in these hundred years has come to occupy a central place in the social sciences.

The most widely accepted definition of attitude among modern theorists, including the five awardees, can be formulated as follows: attitudes are evaluations, positive or negative, that an individual holds towards an object, idea or other individual. Usually expressed in statements of the type “I agree with”, “I like…”, “I want…”, or “I never…,” they help us navigate daily life, informing our choices of what to buy, how to travel to work, where to go on holiday, who to associate with and who to avoid, and how to see others and ourselves.

A given attitude does not immediately give a precise indication of how that person will behave. Indeed this will depend to a large extent on the accessibility of the attitude itself when the individual encounters the object in question (a person, idea, situation). Accessibility is a property of attitudes that denotes the degree of linkage between the object and the evaluative response it meets with. Behavior is likelier to be consistent with attitudes when the attitude is highly accessible – when the linkage is greater. And the principal factors that make an attitude more accessible are it being based on direct, lived experience, having been frequently rehearsed or responding to an evaluation that was not improvised at the point of expression, but is the fruit of reflection by the individual concerned.

Specificity is another key factor for an attitude to accurately predict behavior: the more specific the stimuli driving the attitude, the more consistent with behavior that attitude will be. In opinion surveys, for instance, the more detailed a question is, the better the chance that the attitude expressed will be consistent with subsequent behavior.

Attitudes that explain behavior and provide clues on how to change it

Attitude theory, as the citation remarks, has proved highly influential across a large tract of the social sciences, precisely because of the relationship between attitude and behavior. Icek Ajzen, Professor of Social Psychology, Emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, elaborated on this relationship, with the late Martin Fishbein, in one of social psychology’s most celebrated models for explaining and predicting human behavior: the theory of planned behavior (TPB). This theory, says the committee, “explains how behavior is influenced by attitudes, perceived social pressure, and the difficulty of performing the behavior.”

Ajzen proposed this model in 1985 in a chapter of the book Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior and later developed it in a seminal 1991 paper published in Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. The TPB postulates that a person’s behavior is based on their intention, which rests in turn on three fundamental factors: their attitude towards the behavior in question (positive or negative evaluation towards performing the action); subjective norms (perceived social pressure to act in a given way, based on beliefs about the expectations of family members, friends and society in general); and perceived control of the behavior or self-sufficiency (that is, the individual’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the action, according to the resources, abilities and opportunities at their command).

“In my model,” says Ajzen, “attitudes are one of the three prongs that determine behavior, alongside social influence and the means that a person has to carry it out. The weight of each factor depends on the behavior you’re dealing with and the context.” It has been found, for instance, that in advanced societies like the United States the chance of a person getting vaccinated against a pandemic like COVID 19 “will depend essentially on their personal attitude to that behavior, based on whether they think it is worth getting the jab.” In African countries, conversely, “what counts most is the difficulty. It’s more a question of control, of getting access to the vaccine.”

Ajzen is proud to state that his model has been applied in over 2,000 research projects in the past forty years, and “has shown proven utility in identifying key behavioral factors, and thus developing strategies to modify behavior, in a wide variety of fields with multiple applications.” These run from public health (the promotion of vaccination, the use of condoms to prevent AIDS or the practice of physical activity) to the environment (for example, how to encourage use of public transportation over private vehicles by facilitating citizens’ access to subway or bus lines). “I guess what I’m most proud of is that I developed a model and accompanying methodology that people find useful in their research, no matter what kind of work they do and what kind of behavior they’re interested in. And in fact, it has been applied now quite frequently in behavior change interventions.”

Persuasion: attitudes as a route to behavior change

The relationship between attitudes and behavior can also be studied through the lens of persuasion (understood as a process of social influence over the individual), given its power to alter a person’s attitudes and therefore their behavior. The main persuasion theory proposes two paths to achieve this: the central route, that of more elaboration, using characteristics that demand greater thought on the part of the individual, such that any attitude change will depend on the strength of the argument; and the peripheral route, which asks the recipient to be guided by simple cues without actually analyzing the message. Known as the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), it owes its existence to Richard Petty, working with the late John Cacioppo. “What’s probably the most unique thing about our theory is that it says that the very same variable – whether it’s how much you like the source or how many arguments a source presents – can lead to more influence or less influence depending on the situation; whether the recipient is motivated and able to think about what the source is saying or not. It’s important to understand if someone is going to think a lot or not very much about something to determine how a variable impacts their attitude,” explains Petty, Professor of Psychology at the Ohio State University.

In their book Communication and Persuasion, published in 1986, Petty and Cacioppo focus on the situational and individual factors that drive changes in beliefs, attitudes and behaviors, providing insights into biases, consumer choices, political and legal decision-making and health-related conducts. The ELM, in effect, delves into the basic processes underlying the effectiveness of persuasive messages, identifying the two above routes, along with the diverse antecedents (like personal relevance or the need for cognition) and consequences (attitude stability or behavioral prediction, for example) that favor or result from each. “We discovered that if thinking is responsible for a person’s change, really carefully scrutinizing the information that they receive as opposed to just relying on how much they like the source or how many arguments they are given, the change that’s produced lasts longer and is likelier to impact that person’s behavior.”

The committee says of Richard Petty that “he developed theories regarding how people process persuasive messages and how such processing can lead them to change their attitudes.” The importance of this work is that it helps us understand the role of metacognitive factors, like certainty, and implicit, automatic or unconscious factors in driving attitudinal and behavior extremism and resistance to change, along with the effects of racial and ethnic prejudices, self-validation processes, specific emotions and morality in judgment and social behavior. An understanding that is vital, for, as Petty says “the very same factors that lead people to adopt a moderate opinion might lead them to adopt a more extreme opinion.”

In recent research on the factors conducive to a belief in conspiracy theories, Petty has found that feeling threatened about a particular attitude leads a person to adopt even more extreme positions as a way of reaffirming the strength of their conviction. “Being judged by others, especially if I think those others are looking down on me, is a threat to my view. And so to defend my view or to compensate for that threat, I might adopt a position that’s even more extreme or even favor more extreme behavior.”

Strategies to deal with disinformation and conspiracy theories

The research done by Dolores Albarracín, Alexandra Heyman Nash University Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, “has increased our understanding of how attitudes can be changed, particularly with regard to persuasive messages,” in the words of the award committee.

Martin Fishbein recruited her to be his PhD student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. In 2007 she and Ajzen published Prediction and Change of Health Behavior: Applying the Reasoned Action Approach.

The applied nature of her research is evident in a good number of her published works. These include 2021’s Action and Inaction in a Social World: Prediction and Change of Attitudes and Behaviors, where she shows that appeals to action are more effective than those encouraging inaction when the goal is to achieve a given behavior, and that when a recipient lacks time to analyze a persuasive message, it will be the emotional factor that determines their attitude and behavior.

In 2022 she was among the co-authors of Creating Conspiracy Beliefs: How Our Thoughts Are Shaped, examining ways to discredit disinformation and conspiracy theories. On the latter she has this to say: “In the past conspiracy theories were studied as a function of individual personality, but social psychology has shown that when a belief is taken up by large groups it becomes a problem of social influence.” A society facing more uncertainty is, she reasons, more susceptible to conspiratorial messages, which spread through both interpersonal relationships and other media: “The intentionality of messages of this kind is easier to expose when there is a chance to cross-check and refute them, yet, even so, they are maintained. This happens in the media when the duty to inform is replaced by the desire to indoctrinate; when what they put out has the appearance of news, but is really disinformation.”

For Albarracín, “attitude theory can help us predict the kind of disinformation we have to deal with most urgently. For instance, believing the Earth is flat has no direct impact on a person’s conduct, but believing vaccines are harmful can dissuade someone from getting a jab, with consequences for their own health and public health in general. What the evidence is telling us is that since we can’t stem the whole tide of disinformation, the best strategy is to intervene where it has a direct negative effect.” As to how to intervene, the obvious course is not always the wisest. “Attempting to argue down the misguided belief is just not effective. It’s better to opt for a ‘bypass’ and try to replace that belief by one that holds up, arguing let’s say for the benefits of vaccines or transgenic foods.”

Much of Albarracín’s research has had health implications and her experimental work has been a key input to public health strategies to prevent risk behaviors that bear in mind environmental influence. For nearly two decades, she has received funding from the National Institutes of Health to apply her theoretical findings to the fight against disease in the areas of HIV, smoking and lifestyle change. Examining AIDS prevention campaigns, she concluded that persuasive messages increased people’s knowledge about HIV, but did not lead to behavioral change. Her studies have also found that although fear-based messaging is more effective, a better course is to try to dissuade people from risk behaviors while promoting healthier options.

The unconscious processes that shape attitudes: implicit bias

“Professors Anthony Greenwald and Mahzarin Banaji developed the implicit association test, which enables reliable measurement of implicit bias and its effects on decision-making”. The “implicit bias” the committee refers to was first put forward by Greenwald and Banaji in their 1995 paper “Implicit Social Cognition: Attitudes, Self-esteem and Stereotypes,” published in the journal Psychological Review. In it, the two researchers described what was known about implicit attitudes and stereotypes, while acknowledging that there was as yet no means of measuring them. “We ended that article with a sentence saying that it would really be nice to have a measure that could assess individual differences in implicit attitudes and stereotypes,” Greenwald recalls today.

Armed with this motivation and the work of several decades, the Emeritus Professor of Psychology at the University of Washington came up with a test that measured reaction times in classifying prompts, a method both easy to use and readily obtainable. He called it the implicit association test (IAT) and convinced Banaji and one of her postdoc students Brian Nosek to apply the method in further research.

“We gave people a chance to experience it and they were very surprised by the results,” he relates. “In the first test, we applied what we called the race attitude IAT, which measures associations of black race and white race with pleasant and unpleasant valence or categories. Taking it myself, I discovered I had a stronger association of black with unpleasant than with pleasant and the reverse for white. And that implicit attitude was one that I didn’t at all want to have and in fact didn’t know I had.”

The IAT allows to measure and better understand attitudes that are hard to measure via self-diagnostic techniques, either because the subjects themselves are not aware of their attitudes or because some prejudices, like racism or sexism, are socially frowned on. “We know that these biases kick in at a very young age, from about two years old. And they are also much more widespread in the population than the explicit biases that people admit to in self-report measures; saying, for instance, that men are not better at science than women.”

This method has served as a starting point for numerous applications in clinical psychology, education, marketing and diversity management, and has been used for data collection in over 2,000 papers. Greenwald himself is currently applying the science in a legal context. “After I retired from teaching, I started on a second career in the law courts, helping people who are suing on the basis of discrimination to win their cases using the concepts of implicit bias.”

The story of IAT and its uses was the subject of the book Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People, which Greenwald co-wrote with Mahzarin Banaji. It was subsequently removed from public libraries in a number of U.S. states after being popularized by Hillary Clinton in her 2016 presidential campaign.

From the amygdala to the algorithm: the ubiquity of implicit biases

Mahzarin Banaji is Richard Clarke Cabot Professor of Social Ethics in the Psychology Department at Harvard University. Her research focuses on the disparities between people’s conscious expressions of their values, attitudes and beliefs and the less conscious representation of their mind’s content. As she puts it, “I would say that all the work that I have done in one way or another is to try to get at that invisible but very much present thumbprint of the culture on our brain.” When she convinced Yale University to put the IAT online (in 1998, when the technology was not that widespread), they got 40,000 responses in one month. This tumultuous reception would revolutionize the study of implicit bias. “Every day, I get an email alert about 15 news items that mention the term implicit bias. I would say there is no place I have not seen it used: from the U.S. military to the Museum of Modern Art by way of a garbage collection company. I think that, without knowing, we’ve tapped into something that is fundamental to human nature.”

Besides obtaining an unprecedented volume of data on the implicit biases that affect all corners of society, she has corroborated these results with neuroimaging techniques, observing that the amygdala – the part of the brain that responds to the new or strange – reacts more strongly to black versus white faces the greater the racial bias revealed by the IAT. And she has also been able to show that such biases may not be innate but are nonetheless acquired at a very young age: “Children of six have the same levels of implicit bias as adults.”

Banaji’s work points up a lack of consistency between the values proclaimed at national level and the actual policies that get implemented, as well as between personal values and individual behavior. This has led her to explore the implications of her work for questions of individual responsibility and social justice in democratic societies.

She recently turned her attention to analyzing the presence of these biases in online texts, with worrying results. Using a database of 840,000 words collected in 2014 and 2017, she found that the most frequent associations for “man” or “male” had to do with war and sports, while the words “woman” and “female” were predominantly associated with abuse and pornography, as well as cooking and motherhood. Motivated by these data, she has now focused on analyzing bias in language-based generative artificial intelligence models such as Chat-GPT.

Professor Banaji is now applying the science of social cognition to improve individual decisions and organizational policies. As part of this effort, she has launched a course at Harvard on Outsmarting Implicit Bias, which puts forward strategies to mitigate the effects of implicit bias on individuals and workplace teams. “Becoming educated about bias is imperative and just plain smart. However, I would say diversity training went wrong in a few different ways. It was often preachy. It was rarely evidence based. But when you come to it through the science, humbly, and without judgment, you stand a chance that people with common sense will understand its value.”

Nominators

A total of 45 nominations were received in this edition. The awardee researchers were nominated by Tessa Charlesworth, Donald P. Jacobs Scholar and Assistant Professor at the Kellogg School of Management of Northwestern University (United States); the Department of Psychology at the Ohio State University (United States); Eduardo Fonseca, Vice-Chancellor of Research and Internationalization at the University of La Rioja (Spain); Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Director and Elizabeth Ware Packard Professor of Communication at the Annenberg Public Policy Center and the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania (United States); Benedek Kurdi, Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (United States); and Andrew N. Meltzoff, Job and Gertrud Tamaki Endowed Chair in the Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences at the University of Washington (United States).

Social Sciences committee and evaluation support panel

The committee in this category was chaired by Stephen Sireci, Distinguished University Professor and Executive Director of the Center for Educational Assessment at the University of Massachusetts Amherst (United States), with José Muñiz, the Chancellor of Nebrija University and Professor of Psychometrics at the University of Oviedo acting as secretary.

Remaining members were Matilde Carlón, Professor of Administrative Law at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) (Spain); Roberto Colom, Professor of Differential Psychology at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM) (Spain); Catherine E. De Vries, Professor of Political Science and Generali Chair in European Policies at Bocconi University (Italy); and Jorge Fernández del Valle, Professor of Social Psychology at the University of Oviedo (Spain).

The evaluation support panel of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) was coordinated by Elena Cartea, Deputy Vice-President for Scientific-Technical Areas at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and Sebastian Rinken, Tenured Scientist at the Institute of Advanced Social Studies (IESA, CSIC), and formed by: Héctor Cebolla Boado, Scientific Researcher at the Institute of Economics, Geography and Demography (IEGD-CCHS, CSIC); Marta Fraile Maldonado, Tenured Scientist and Deputy Director at the Institute of Public Goods and Policies (IPP-CCHS, CSIC); and Ana López Sala, Scientific Researcher at the Institute of Economics, Geography and Demography (IEGD-CCHS, CSIC).