The Frontiers of Knowledge Award goes to Blanchard, Galí and Woodford in recognition of their profound influence on modern macroeconomics and the design of monetary and fiscal policy rules

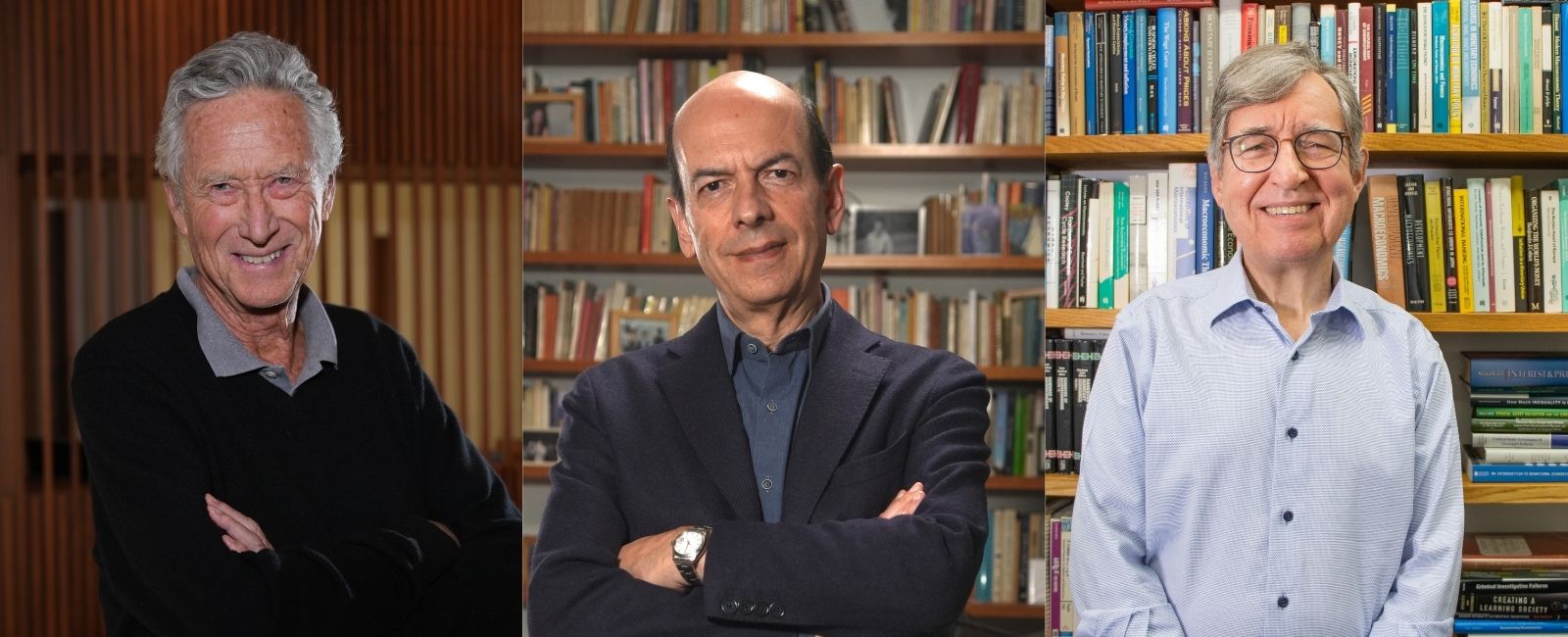

The BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Awards in Economics, Finance and Management has gone in this seventeenth edition to Olivier Blanchard (Paris School of Economics and MIT), Jordi Galí (CREI and Pompeu Fabra University), and Michael Woodford (Columbia University) for “profoundly influencing modern macroeconomic analysis by establishing rigorous foundations for the study of business cycle fluctuations.”

25 February, 2025

The committee hailed the three economists as “central architects of the New Keynesian paradigm” for integrating “monopolistic competition and nominal and real rigidities into dynamic general equilibrium models with rational expectations.” This paradigm, they added, “has been widely used to analyze the stabilizing effect of monetary and fiscal policy on the cyclical movements of real economic activity, unemployment, and inflation.”

This combination of academic research and influence on policy design has meant that the model they constructed “is used by central banks the world over in their monetary policy decision-making and has become a teaching staple in degree courses everywhere,” said committee member Antonio Ciccone, Professor of Macroeconomics and Financial Markets at the University of Mannheim (Germany).

“They put the pieces in place for a new model that seeks to avoid business cycle fluctuations and keep unemployment or inflation at relatively stable levels,” explained Fabrizio Zilibotti, Professor of International and Development Economics at Yale University (USA), and also a selection committee member. “The New Keynesian theory,” he continued, “emphasizes the role of expectations, which were essentially left out of traditional models. In this model, demand depends on expectations of the future course of the economy. In other words, it looks to the future to make decisions in the present. This is the opposite of the classical models, which decide measures in the present by looking at events in the past.”

The New Keynesian economics and monetary policy

In the early 1980s, Olivier Blanchard found himself moving between appointments at Harvard and MIT. It was in these years that he came to know Jordi Galí and Michael Woodford, leaving a lasting impression as thesis advisor to the former and as a “brilliant young teacher” in the recollection of the latter. By that time, he had already authored a number of seminal articles on speculative bubbles and their impact on macroeconomic cycles.

Blanchard’s founding role in New Keynesian economics can be traced to a joint 1987 paper with Nobuhiro Kiyotaky (Frontiers of Knowledge laureate in Economics in the 13th edition of the awards), where they studied the effects of monetary policy under monopolistic competition. What they found was that nominal rigidities acted as a major distorting factor: when consumers turn pessimistic and cut back on their spending, aggregate output falls. In the absence of nominal rigidities, what would happen is that interest rates would be adjusted so they keep on buying enough to stop the economy from entering recession. But with nominal rigidities this mechanism cannot work.

“What we argued,” says Blanchard in regard to this landmark work, “was that there was a price externality in the sense that in an environment of imperfect competition, price setters had very little incentive to change their prices in response to demand. But the result of each price not changing was that the price level didn’t move, and this led the demand effect to fall on output rather than on prices. I think our contribution was more to clarify the mechanism, but the paper was very influential.”

In 1997, Michael Woodford co-authored a paper with Julio Rotemberg in which they made an econometric estimation of a quantitative model in the New Keynesian framework, laying a number of key theoretical grounds for the development of the New Keynesian model of monetary policy.

Two years later, Jordi Galí partially extended and synthesized this theoretical framework. The Catalan researcher published an article with Mark Gertler (Frontiers of Knowledge laureate in Economics in the 13th edition of the awards) and Robert Clarida, in which they turned their attention to the Taylor Rule, a set of functions relating inflation, interest rates and another economic variable which could be GDP growth or aggregate demand. The result was a guideline for central banks to design the best monetary policy for a given period.

“The basic New Keynesian model consists of three equations,” Professor Galí explains. “The first describes the behavior of economic activity as a function of the interest rate. The second describes how inflation will perform as a function of the level of activity. And, finally, we have a third equation describing the behavior of the monetary authority – that is, the monetary policy rule being implemented by the central bank.”

Unconventional monetary policies

“The importance of the Taylor Rule,” Professor Woodford reflects, “is that it led to a renaissance of research by academic monetary economists in studying actual central bank behavior and trying to use sophisticated models to think about the effects of more realistic specifications of monetary policy.”

In a few short years, this analysis would find practical expression in the unconventional monetary policies that dominated the response to the financial crisis of the start of this century. In Galí’s words: “Woodford’s contributions are a key input to the design of the policies followed by leading central banks when interest rates reach zero, so have no more room to fall.”

The first time they were wielded was in 2002, after the dotcom bubble burst. The U.S. economy was struggling to pull clear of recession and deflation risk loomed large. The Federal Reserve had already cut rates as far as they thought possible and its governors believed they had used up all scope for monetary policy manoeuver, until Michael Woodford convinced them otherwise. In summer 2003, he recalls today, “they decided to experiment, I think successfully” with the use of forward guidance, managing expectations on future policy rates. Specifically, they announced their intention to keep interest rates low for a considerable period until certain economic conditions were fulfilled.

The pillar of this approach is that an important part of what central banks do should be to communicate the likely future path of monetary policy to private economic agents. “Before the 2000s,” says Woodford, “it was commonly accepted by central banks that they should make decisions about how to intervene in markets, but they didn’t need to talk to the public at all about what they were doing, and certainly not to give any hints in advance about what they might do in the future. The idea of forward guidance instead argues that in addition to directly intervening in markets, it’s very important what central banks say to people, not just while they’re doing it, but to give them an idea of what they expect to do further down the road, perhaps months or even years into the future.”

When the financial crisis erupted in 2008, these policies had already been tested in a real-world situation, enabling the Federal Reserve to react quickly, implementing both forward guidance and quantitative easing, buying up large quantities of government securities. At around the same time, Olivier Blanchard was taking up the post of economic counsellor with the International Monetary Fund. During his tenure there, he had multiple occasions to apply the models he had helped devise, seeking to give context to the current juncture and outline alternative strategies. Through these critical insights he was able to shape policies at a vital time and contribute centrally to modern economic analysis.

Nominators

A total of 64 nominations were received in this edition. The three laureates were nominated by: Samuel Bentolila, Professor of Economics at the Center for Monetary and Financial Studies (CEMFI) of Banco de España (Spain); Juan Francisco Jimeno, an advisor at Banco de España (Spain); Klaus Adam, Head of the Department of Economics at the University of Mannheim (Germany); Florin O. Bilbiie, Professor of Macroeconomics at the University of Cambridge, Senior J. M. Keynes Fellow, and Janeway Institute Theme Coordinator (United Kingdom); Teresa Garcia-Milà, Director of the Barcelona School of Economics (Spain); Mark Gertler, Henry and Lucy Moses Professor at New York University (United States); Marek Jarociński, Lead Economist at the European Central Bank (Germany); Peter Karadi, Lead Economist at the European Central Bank (Germany); Anton Nakov, Principal Economist at the European Central Bank (Germany); Kalin Nikolov, Head of Section in the Directorate General of Research and Innovation of the European Central Bank (Germany); Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé, Professor of Economics at Columbia University (United States); and Jaume Ventura, Director of the Centre de Recerca en Economia Internacional, CREI (Spain).

Economics, Finance and Management committee and evaluation support panel

The committee in this category was chaired by Eric S. Maskin, Adams University Professor in the Department of Economics at Harvard University (United States) and 2007 Nobel Laureate in Economic Sciences, with Manuel Arellano, Professor of Economics in the Center for Monetary and Financial Studies (CEMFI) of Banco de España acting as secretary.

Remaining members were Sir Richard Blundell, David Ricardo Professor of Political Economy at University College London (United Kingdom) and 2014 BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Laureate in Economics, Finance and Management; Antonio Ciccone, Professor of Economics at the University of Mannheim (Germany); Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg, Elihu Professor of Economics and Global Affairs at Yale University (United States); Andreu Mas-Colell, Professor Emeritus of Economics at Pompeu Fabra University and the Barcelona School of Economics (Spain) and 2009 BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Laureate in Economics, Finance and Management; Lucrezia Reichlin, Professor of Economics at the London Business School (United Kingdom); and Fabrizio Zilibotti, Tuntex Professor of International and Development Economics at Yale University (United States).

The evaluation support panel was coordinated by Elena Cartea, Deputy Vice-President for Scientific-Technical Areas at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), and Joan Llull Cabrer, Research professor at the Institute for Economic Analysis (IAE, CSIC). Its members were: Inés Macho Stadler, Professor of Economics in the Economic Sciences Faculty at the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona; Laura Mayoral Santamaría, Scientific Researcher at the Institute for Economic Analysis (IAE, CSIC); Xavier Ramos Morilla, Associate Professor in the Department of Applied Economics at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; and Virginia Sánchez Marcos, Professor of Fundamentals of Economic Analysis in the Department of Economics of the University of Cantabria (UNICAN).